Sleep is supposed to be restorative, but nearly a billion adults around the world experience disruptions in their breathing during sleep, and the problem affects more than half of people in some countries. In addition to snoring, struggling to breathe during sleep can lead to a variety of health consequences, including higher risks for heart disease, diabetes, arrhythmias, and traffic accidents.

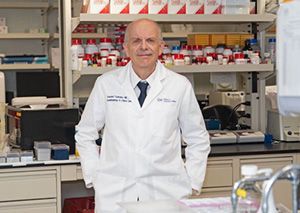

Although sleep-disordered breathing is a widespread and growing problem, treatments are lacking, says Vsevolod “Seva” Polotsky, MD, vice chair for research in the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine. The main treatment strategy — breathing machines known as CPAPs — work for only about half of people; the rest never manage to get used to it. There is a surgery to implant a nerve stimulator that opens the airway, but it is expensive and invasive. Otherwise, there are no FDA-approved medications.

Polotsky and his research team are trying to fill the treatment gap by getting to the core of the problem, understanding the basic science behind how breathing and sleep work in the brain, and translating that research into new applications. His work focuses on two separate but related issues: obesity and opioid use. Both are common causes of sleep-disordered breathing, and people with obesity experience more pain and more frequently require opioid prescriptions.

Bridging the Gap Between Science and Medicine

After coming to the United States from Russia in 1991, Polotsky completed extensive research training, including fellowships and medical residencies in both pulmonary critical care and sleep medicine. He spent 24 years at Johns Hopkins University before coming to George Washington University at the end of 2022. His position as vice chair for research in the department is a collaborative role. One of his main goals is build a basic research program that will feed into the department’s strong portfolio of clinical research, contributing discoveries that could lead to new treatments for sleep-disordered breathing and opioid use disorder.

Through his research, Polotsky is also striving to bridge a gap between basic science and clinical medicine — two worlds that don’t always communicate enough with each other. He once talked with a renowned neuroscientist who had discovered the neurons that regulate breathing. Polotsky asked him why he didn’t collaborate with sleep medicine practitioners at his institution.

“He said, ‘I don’t know who they are and they have no idea who I am,’ ” Polotsky says. “There is a huge gap between basic science and clinical medicine in our field. My lab is trying to bridge it.”

One of the most promising avenues of research involves leptin, a hormone that is involved in both appetite and energy use. Through novel ways of delivering leptin to the brain, among other strategies, Polotsky is making encouraging discoveries that could offer relief to people with sleep-disordered breathing as a result of obesity and opioid use, potentially helping many millions of people. Because people with breathing problems often miss work, better treatments could also have a significant financial impact.

“Can you imagine a truck driver who can’t use a CPAP? They will lose their job if they cannot get treatment,” Polotsky says. “It is important to search for new drugs.”

Understanding Sleep-Disordered Breathing

Early in his career in the 1990s, Polotsky noticed that intensive care patients with obesity had many unexplained complications, including airway management challenges. They had a hard time getting onto ventilators, and equally hard getting off the machines. The field of sleep-disordered breathing was still new, and Polotsky became interested in the emerging understanding of how obesity was related to breathing problems during sleep and related health care challenges.

Today, researchers have identified three main conditions that account for most cases of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. The most common is obstructive sleep apnea, which is a recurrent closure of the throat during sleep, often as a result of a combination of anatomical issues and inadequate function of the upper airway muscles. Central sleep apnea is related, but caused by a failure of the body to try to breathe. A third cause, called obesity hypoventilation syndrome, results from accumulating levels of carbon dioxide in the blood that can become life-threatening. Obesity raises the risk for all three. Some 70% of people with obstructive sleep apnea, for instance, are obese.

Leptin, discovered in 1994 around the same time as sleep-disordered breathing was emerging as a field, became one of the first and most tantalizing targets of treatment for both obesity and sleep-related breathing problems. The hormone, which is produced by fat cells called adipocytes, normally suppresses appetite and increases energy use. It also affects sleep-disordered breathing by influencing the body’s regulation of muscles and processes related to respiration, according to Polotsky’s early research. Subsequent studies have shown when mice lack leptin they become obese and develop breathing problems during sleep. Giving the hormone to a leptin-deficient mouse, on the other hand, causes it to eat less, lose weight, and breathe better. Those discoveries fueled hopes that leptin might be helpful for people, too.

Instead, Polotsky says, studies show that most people with obesity produce high levels of leptin, but it can’t get from the blood into the brain to affect metabolic processes. This recognition of leptin resistance has led to a new line of research focused on delivering leptin to the brain, where it might help with sleep-disordered breathing, and not just when it’s related to obesity.

New Approaches to Better Breathing During Sleep

To bypass the blood-brain barrier and get leptin directly to where it could work its magic, Polotsky and colleagues squirted leptin into the noses of obese mice that, like people, had both leptin resistance and sleep-disordered breathing. In 2019, the team reported that a single dose of leptin led to significant improvements in breathing during sleep in the animals. Taken through the nose, Polotsky says, the hormone travels along nerves and lymphatic vessels directly into the brain.

Establishing that intranasal leptin could effectively overcome obesity-related sleep-disordered breathing opened another possibility — maybe leptin might also help with other causes of breathing disturbances during sleep, including opioid use.

Respiratory depression, especially during sleep, is the main cause of death associated with opioids, and people with obesity are particularly vulnerable because of their already-elevated risk for sleep-disordered breathing.

Hoping to test the potential for leptin to help, Polotsky and colleagues gave morphine to obese mice along with either intranasal leptin or a placebo nasal spray. On its own, they reported in 2020, the opioid dramatically increased the frequency and severity of sleep apnea. But when the mice also got leptin, their breathing during sleep improved.

The results, Polotsky says, suggest that intranasal leptin could be lifesaving if given as a prophylactic along with high doses of prescription opioids in medical settings.

Unlike naloxone, a drug that reverses opioid overdoses, leptin does not counteract the pain-relieving effects of the drugs, and it is longer lasting. Leptin will probably not become a replacement for naloxone as an overdose treatment, Polotsky adds, but he would like to test the effects of using both drugs together.

Polotsky is now working, supported by multiple grants, to better understand the role of leptin in sleep-disordered breathing associated with both obesity and opioid use. Among his avenues of research, he is exploring ways to influence leptin receptors in the brain, and he is investigating molecules affected by leptin. Just like there are multiple classes of drugs to treat hypertension, sleep-disordered breathing will likely require a variety of strategies to help the most people. “Sleep-disordered breathing and opioid-induced respiratory depression are both complex conditions, and they will need multiple approaches,” Polotsky says. “This story is evolving.”